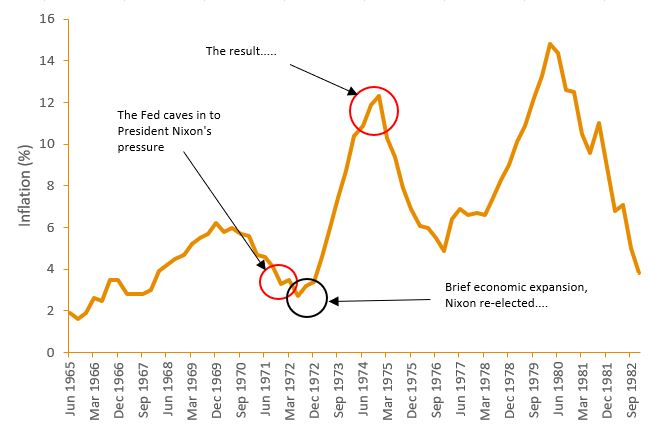

Major central banks around the globe have, for some time now, been granted total independence in making monetary policy decisions in an effort to ensure the prioritisation of long-term economic health over more short-sighted decisions for political motives. President Trump’s comments last week that he is “not thrilled” by recent increases in the Federal Reserve’s Funds rate has broken the long-held convention by US presidents to abstain from publicly remarking on the central bank’s monetary policy decisions. Such comments have brought the long-dormant discussion of central bank independence back into question amid market concerns that the president’s comments and clear preference for lower interest rates could place Fed Reserve Governor Jerome Powell in a precarious situation in an effort to underline the Fed’s independence. In the US, the Humphrey-Hawkins Act requires the Federal Reserve to conduct monetary policy to promote the goals of ‘maximum employment, stables prices, and moderate long-term interest rates’ – not alleviate the governments concerns that higher costs of borrowing will subdue economic growth. The US president is perhaps coming precariously close to falling into the same trap as leaders past who have put their own short-term interests ahead of their countries long-term stability. When looking through history for implications from leaders who taken similar stances, one does not have to look too far back. As recently as May, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan made his opposition of rising interest rates clear to Turkey’s central bank in order to fuel further credit growth and construction, ignoring key economic indicators and arguing against conventional economic theory that lowering interest rates will encourage further growths in inflation. Fast forward two months and the country is on the verge of a corporate debt crisis after the Turkish Lira has depreciated by over 20% YTD against the USD (Figure 1) with Turkish firms struggling to repay an estimated $20 billion in foreign currency loans. Figure 1: Turkish Lira/USD Cross Rate YTD  In the Trash In addition to the woes facing its private sector, the Turkish government has its fair share of problems of its own direct making, with ~40% of outstanding debt denominated in foreign currencies. As a consequence, the country’s sovereign debt rating has been downgraded for the second time in as many years to BB-/B from BB/B by S&P, three notches below investment grade for S&P and two notches below for Moody’s – well into junk territory. In a statement S&P reflected the above points, citing concerns over a “deteriorating inflation outlook” and “risk of a hard landing for Turkey’s overheating, credit-fuelled economy”. Of particular concern, is the rating agencies comments that the central banks reluctance to aggressively tighten policy in the face of double-digit inflation has increased concerns that it has been facing “increasing political pressure” – i.e. the Turkish central bank’s actual independence is under threat. Closer to Home In another example of the dangers that this line of thought can pose, the President must only look to the actions that occurred in the very office that he currently resides in by another US president in the early 1970’s – Richard Nixon. Amid fears over his re-election in 1972, the president expressed concerns towards raising interest rates to Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns. Succumbing to pressures from the White House, the fed reversed its interest rate path in late 1971 and surely enough, after experiencing a short-lived fall in unemployment and a growing economy in 1972, the economy then fell into recession in 1973 with exorbitantly high inflation that soared as high as 12% – plaguing the US’ economy for a decade afterwards in a period which became known as “The Great Inflation” (Figure 2). Figure 2: “The Great Inflation”

In the Trash In addition to the woes facing its private sector, the Turkish government has its fair share of problems of its own direct making, with ~40% of outstanding debt denominated in foreign currencies. As a consequence, the country’s sovereign debt rating has been downgraded for the second time in as many years to BB-/B from BB/B by S&P, three notches below investment grade for S&P and two notches below for Moody’s – well into junk territory. In a statement S&P reflected the above points, citing concerns over a “deteriorating inflation outlook” and “risk of a hard landing for Turkey’s overheating, credit-fuelled economy”. Of particular concern, is the rating agencies comments that the central banks reluctance to aggressively tighten policy in the face of double-digit inflation has increased concerns that it has been facing “increasing political pressure” – i.e. the Turkish central bank’s actual independence is under threat. Closer to Home In another example of the dangers that this line of thought can pose, the President must only look to the actions that occurred in the very office that he currently resides in by another US president in the early 1970’s – Richard Nixon. Amid fears over his re-election in 1972, the president expressed concerns towards raising interest rates to Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns. Succumbing to pressures from the White House, the fed reversed its interest rate path in late 1971 and surely enough, after experiencing a short-lived fall in unemployment and a growing economy in 1972, the economy then fell into recession in 1973 with exorbitantly high inflation that soared as high as 12% – plaguing the US’ economy for a decade afterwards in a period which became known as “The Great Inflation” (Figure 2). Figure 2: “The Great Inflation”  Whilst the trials and tribulations of Turkey and 1970’s America can be viewed as extremes, they highlight the importance of central bank independence and the potentially devastating ramifications that outside influences can have on an economy. There are of course many other examples of central banks making mistakes, not acting promptly enough or too late for changes to take effect, at least they were their own errors and made by a committee with the best intentions. If anything, the offshore mutterings and possible tinkerings by politicians should serve as a sobering reminder that with a plethora of central banks scheduled to make announcements this week, it is probably best to place faith in the experts and the data. For the RBA, which will later this year probably pass the 2-year mark of stable rates, one could well imagine a curt reply to any politician trying to dabble in rate-settling as “can’t help you mate – we’ve forgotten how to change rates”.

Whilst the trials and tribulations of Turkey and 1970’s America can be viewed as extremes, they highlight the importance of central bank independence and the potentially devastating ramifications that outside influences can have on an economy. There are of course many other examples of central banks making mistakes, not acting promptly enough or too late for changes to take effect, at least they were their own errors and made by a committee with the best intentions. If anything, the offshore mutterings and possible tinkerings by politicians should serve as a sobering reminder that with a plethora of central banks scheduled to make announcements this week, it is probably best to place faith in the experts and the data. For the RBA, which will later this year probably pass the 2-year mark of stable rates, one could well imagine a curt reply to any politician trying to dabble in rate-settling as “can’t help you mate – we’ve forgotten how to change rates”.