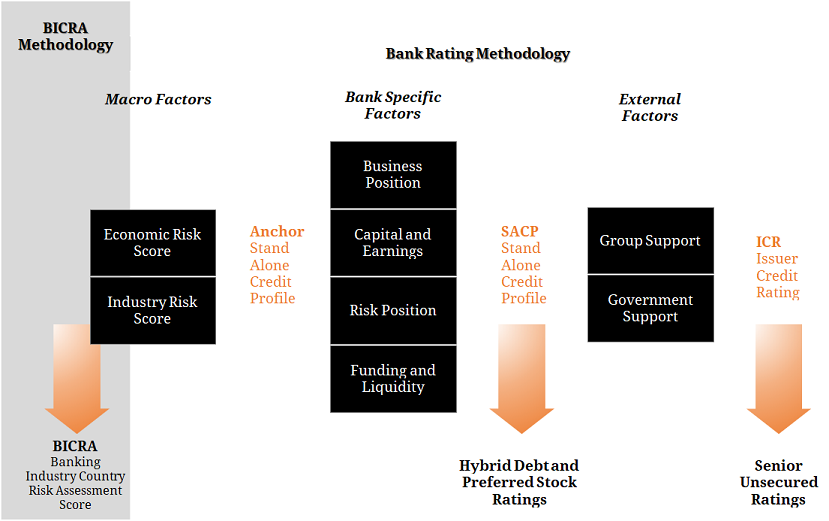

On the 22nd of May 2017, Standard and Poor’s (S&P) announced the Issuer Credit Ratings of 23 Banks (both domestic and foreign branches) operating in Australia would be downgraded due to concerns around potential economic imbalances. While there has been a lot of coverage around the potential consequences of this rating action, we believe it is important to break down the underlying rating methodology to assist investors with a better understanding of the downgrade. The S&P Rating Methodology for Banks consists of two key steps:

- Determining the Stand Alone Credit Profile (SACP) of the issuer

- Establishing the likelihood of extraordinary support to determine the bank’s Issuer Credit Rating (ICR)

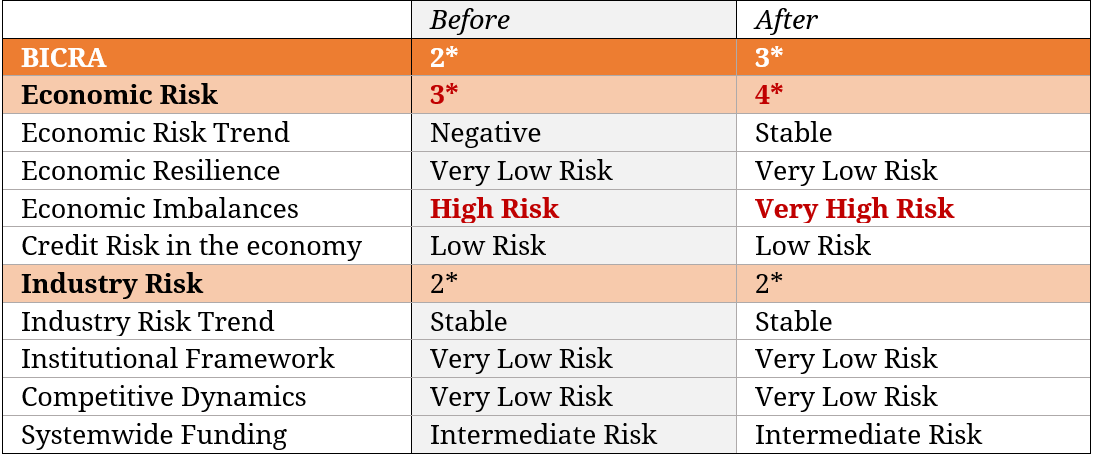

Figure 1. S&P Bank Ratings Framework  Source: S&P “Banks: Ratings Methodology and Assumptions”, 9 Nov 2011 The downgrade was a result of S&P’s downward revision to Australia’s Banking Industry Country Risk Assessment (BICRA) from ‘2’ to ‘3’. This was primarily driven by the Economic Risk score falling from ‘3’ to ‘4’ due to higher imbalances from mounting house price growth and household leverage (See Figure 2). Figure 2: S&P’s BICRA Rating Snapshot

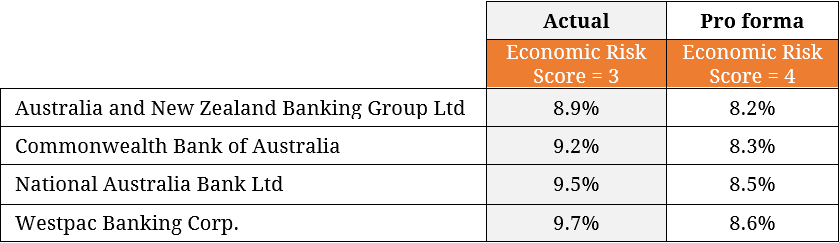

Source: S&P “Banks: Ratings Methodology and Assumptions”, 9 Nov 2011 The downgrade was a result of S&P’s downward revision to Australia’s Banking Industry Country Risk Assessment (BICRA) from ‘2’ to ‘3’. This was primarily driven by the Economic Risk score falling from ‘3’ to ‘4’ due to higher imbalances from mounting house price growth and household leverage (See Figure 2). Figure 2: S&P’s BICRA Rating Snapshot  *Scale of 1 (lowest risk) to 10 (highest risk) Source: S&P Global Ratings The higher economic risk score (which implies increased economic risk) translates into higher risk-weights for the banks’ assets (loans) in the calculation of S&P’s projected risk-adjusted capital ratio (RAC). With this adjustment, the proforma capital ratios for the major banks are now lower: Figure 3. Major Bank Risk Adjusted Capital ratios for FY16

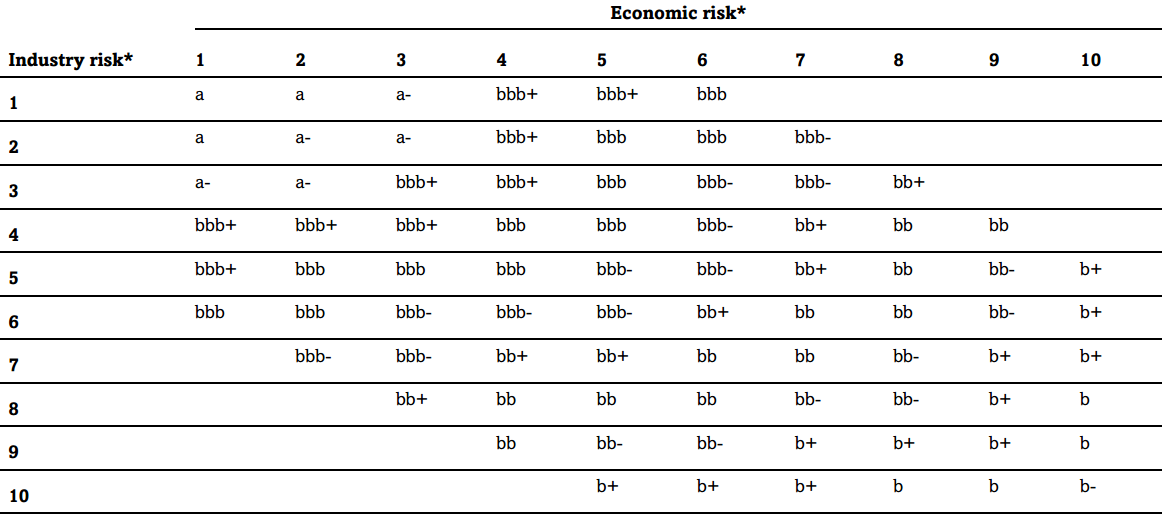

*Scale of 1 (lowest risk) to 10 (highest risk) Source: S&P Global Ratings The higher economic risk score (which implies increased economic risk) translates into higher risk-weights for the banks’ assets (loans) in the calculation of S&P’s projected risk-adjusted capital ratio (RAC). With this adjustment, the proforma capital ratios for the major banks are now lower: Figure 3. Major Bank Risk Adjusted Capital ratios for FY16  Source: S&P Global Ratings, Bank Disclosures Despite elevated systemic risk, the agency recognised the domestic regulator’s (APRA) recent macroprudential action to curb vulnerabilities in the property market (30% cap on higher risk interest-only loans) should aid in “unwinding of the imbalances in an orderly fashion”. S&P also indicated that it would revisit the current ratings if the RAC ratios of these banks sat comfortably above 10%, which could come from the implementation of APRA’s anticipated ‘unquestionably strong’ capital standards. The BICRA’s economic risk and industry risk scores are used to determine the bank’s anchor SACP (see Figures 1 & 4), the starting point in assigning an Issuer Credit Rating. This is then adjusted up or down the ratings scale after taking into account a bank’s specific strengths and weaknesses in the following factors, which will equate to an individual bank’s SACP:

Source: S&P Global Ratings, Bank Disclosures Despite elevated systemic risk, the agency recognised the domestic regulator’s (APRA) recent macroprudential action to curb vulnerabilities in the property market (30% cap on higher risk interest-only loans) should aid in “unwinding of the imbalances in an orderly fashion”. S&P also indicated that it would revisit the current ratings if the RAC ratios of these banks sat comfortably above 10%, which could come from the implementation of APRA’s anticipated ‘unquestionably strong’ capital standards. The BICRA’s economic risk and industry risk scores are used to determine the bank’s anchor SACP (see Figures 1 & 4), the starting point in assigning an Issuer Credit Rating. This is then adjusted up or down the ratings scale after taking into account a bank’s specific strengths and weaknesses in the following factors, which will equate to an individual bank’s SACP:

- Business position;

- Capital and earnings;

- Risk position;

- Funding and liquidity.

Figure 4. Determining the SACP from Economic and Industry Risk  *Scale of 1 (lowest risk) to 10 (highest risk) Source: S&P Global Ratings Relative to the SACP, the rating for senior unsecured and hybrid debt works on a notching basis (up for senior debt and down for Tier 2 and Tier 1 capital instruments). Senior debt is given an uplift if the agency believes these companies are too big to fail (i.e. major banks) and hence, in a stressed scenario the government will provide support. On the other hand, they do not expect the government to step in for capital instruments if there is a bank failure (i.e. point of non-viability) which is reason these securities are notched down. As a result, the next step is determining the ICR of the bank is by assessing the likelihood of future extraordinary support from the government or parent and how this relationship alters a bank’s overall credit risk. In practice, a bank normally receives help from either its parent group or government. Accordingly, a bank that is a operating subsidiary receives the higher indicative ICR resulting from the group support framework (Macquarie Bank, Suncorp-Metway) or the government support framework (the Major Banks). Additional loss-absorbing capital (ALAC) is the third form of extraordinary support, alongside government or group support but this is yet to become a factor for Australian banks. In a financial crisis, a government will often (but not always) provide additional support if it believes damage to the economy outweighs the cost to taxpayers. Currently, the four major banks enjoy a 3 notch (the highest) uplift in the ICR stemming from government support (See Figure 5). Figure 5. Likelihood of Government Support

*Scale of 1 (lowest risk) to 10 (highest risk) Source: S&P Global Ratings Relative to the SACP, the rating for senior unsecured and hybrid debt works on a notching basis (up for senior debt and down for Tier 2 and Tier 1 capital instruments). Senior debt is given an uplift if the agency believes these companies are too big to fail (i.e. major banks) and hence, in a stressed scenario the government will provide support. On the other hand, they do not expect the government to step in for capital instruments if there is a bank failure (i.e. point of non-viability) which is reason these securities are notched down. As a result, the next step is determining the ICR of the bank is by assessing the likelihood of future extraordinary support from the government or parent and how this relationship alters a bank’s overall credit risk. In practice, a bank normally receives help from either its parent group or government. Accordingly, a bank that is a operating subsidiary receives the higher indicative ICR resulting from the group support framework (Macquarie Bank, Suncorp-Metway) or the government support framework (the Major Banks). Additional loss-absorbing capital (ALAC) is the third form of extraordinary support, alongside government or group support but this is yet to become a factor for Australian banks. In a financial crisis, a government will often (but not always) provide additional support if it believes damage to the economy outweighs the cost to taxpayers. Currently, the four major banks enjoy a 3 notch (the highest) uplift in the ICR stemming from government support (See Figure 5). Figure 5. Likelihood of Government Support  Source: S&P “Banks: Ratings Methodology and Assumptions”, 9 Nov 2011 Overall, the framework and recent rating action indicates S&P is currently being prescriptive in its actions with regards to banks and that the downgrade was primarily driven by top down systemic leverage rather than the bottom up results of the banks. This highlights the current gap in the risk tolerance between the regulators and credit rating agency, which may be become better aligned once the APRA’s capital adequacy framework is finalised in the coming months.

Source: S&P “Banks: Ratings Methodology and Assumptions”, 9 Nov 2011 Overall, the framework and recent rating action indicates S&P is currently being prescriptive in its actions with regards to banks and that the downgrade was primarily driven by top down systemic leverage rather than the bottom up results of the banks. This highlights the current gap in the risk tolerance between the regulators and credit rating agency, which may be become better aligned once the APRA’s capital adequacy framework is finalised in the coming months.